Jagraj Singh, 1979 - 2017: a British Sikh pioneer and educator

(Jagraj Singh, speaking into the megaphone)

(Jagraj Singh, speaking into the megaphone)

“Why do they want to kill the Sikhs? The reason they want to kill the Sikhs is because we are trying to change the world,” Jagraj Singh is seen shouting into the speaker. The video is from 2016, at a march to remember Sikh victims of the 1984 pogroms. He continues: “Guru Sahib has told us - where ever we are, take hold of power and change! For whom? Change not for our benefit but… working for the benefit of everyone. Giving food, giving justice to everyone. Sikhs are the ones who are willing to put their lives on the line to give other people freedom.”

It was Jagraj at his best: comfortably speaking to and whipping up a large crowd about Sikhism’s message of social justice, calling on them to become even more politicised than they already were. They lapped it up of course.

In a short space of time, my younger brother had become one of the most popular and recognisable Sikh activists and preachers in Britain, if not the world. Even some of my friends started telling me how much they enjoyed his videos. He had become a phenomenon.

In late 2016, he was diagnosed with cancer (stage 4), given barely three months to live. When he held a public event after that, so many people came to pay their respects that there was no standing space inside the large Gurdwara hall in west London. Thousands more watched him on a live-stream talking about his illness.

Barely a month after his wife gave birth to their third child, a girl, Jagraj Singh passed away last week. Friday was his funeral.

Before I go any further I should explain myself. It is extremely painful to write your own brother’s obituary but it is the only form of expression I have. This is neither a full account of his life nor a homage from a fan. This is the perspective of someone who knew him longest and loved him deeply, as a brother but also a critic. Even though our views had increasingly diverged in the last few years, we put aside our differences after he was diagnosed with cancer.

So why am I writing this? This is partly a tribute and partly an explanation. The story of Jagraj Singh is also the story of how the British Sikh community has evolved over the years and where its heading.

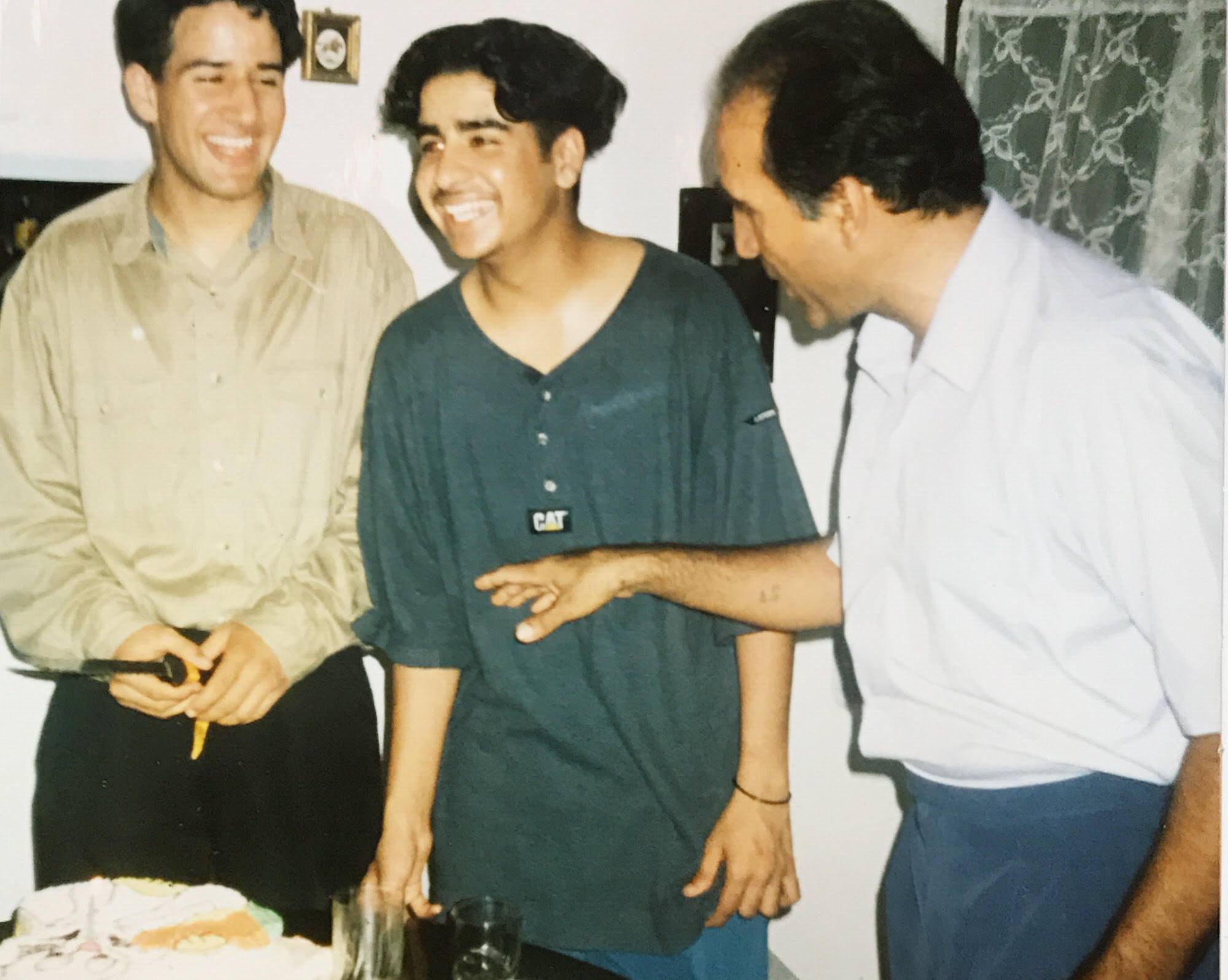

Jagraj's 16th birthday (me on the left, our father on the right)

Jagraj's 16th birthday (me on the left, our father on the right)

The Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu famously wrote that the flame that burns twice as bright burns half as long. But Jagraj was more a burning planet than just a flame. He created his own orbit and pulled in others through sheer force of gravity.

He was born in London in 1979. Both of us brothers moved between India and Britain until we were teenagers, before finally settling down in London. We shared a room in a small council flat, which didn’t make it easy for two stubborn brothers to get along. Our parents raised him with long hair but not me. In a quirk of fate and symmetry, while I went through a brief phase of growing my hair, he went through a brief phase of having it cut short.

He was also very accident prone. He had stitches all over his body from dangerous incidents that could have been easily avoided. Once, a metal shard flew into his leg when we were blowing up tin-cans with big Diwali firecrackers in India. The poor guy had to be stitched up without an anesthetic. Another time he landed in hospital when my bicycle rammed into his after he braked too quickly.

Though I wouldn’t admit it to him, he was also the cooler younger brother. He introduced me to RnB and hip-hop, to trendy and baggy jeans (it was the 80s and early 90s, okay), to computer games. He was way better at chatting up girls than I was.

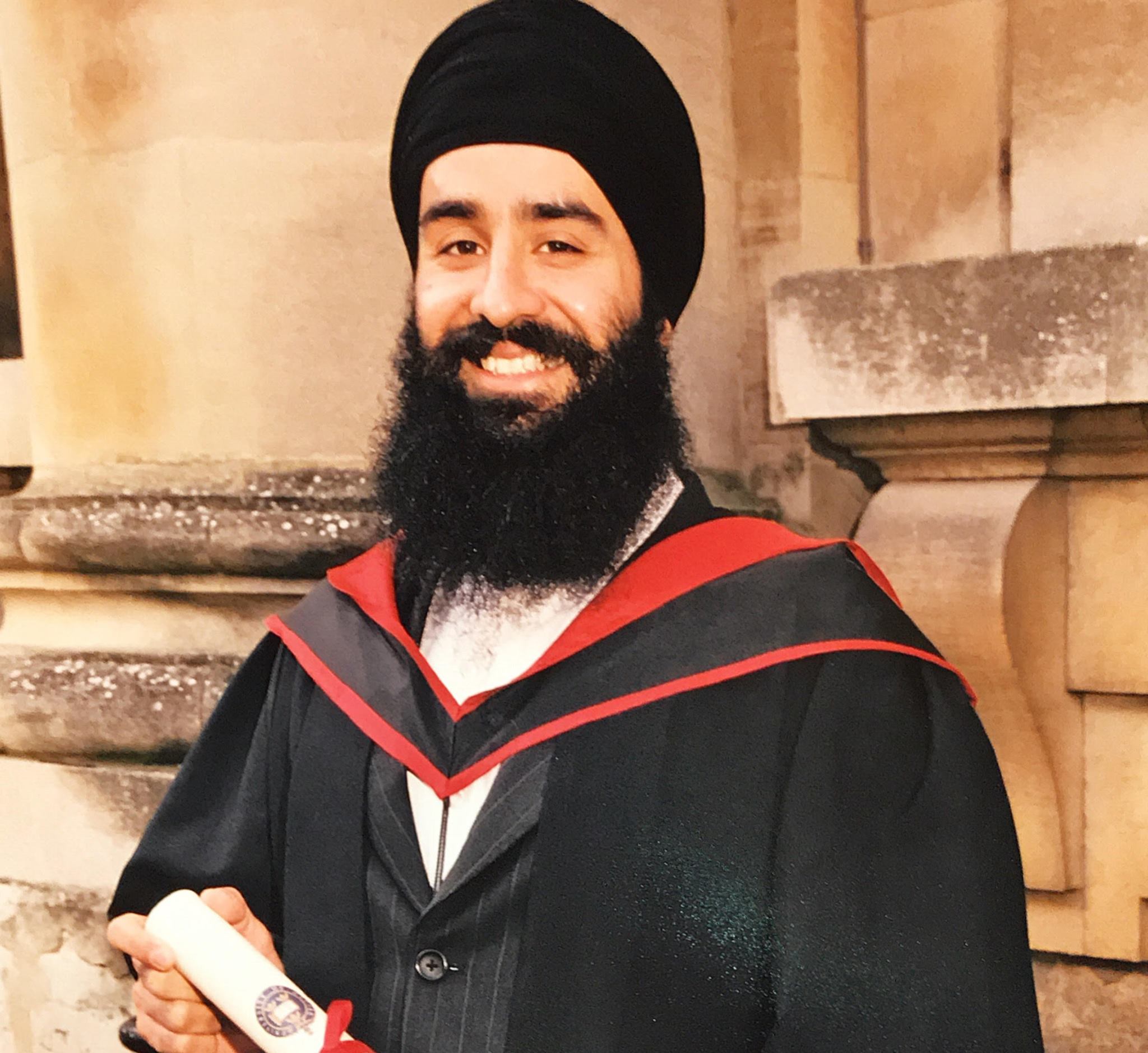

Graduation

Graduation

Some say his journey into Sikhism began when he started his degree (PPE) at Oxford University. But people forget that our past usually shapes our future. Sikhism gave him a purpose and a sense of stability that a previous life of excessive partying and boozing never did.

He wasn't alone in this journey either. From around the mid-90s, when second-generation (born and bred here) British Asians started attending universities in large numbers, many of them started to embrace religion. There was this hunger for a more puritanical religious identity amongst our generation that even took our parents by surprise. It was mostly prevalent among Muslims and then Sikhs. Less so with Hindus. (It would take a much longer article to explore why this was happening).

Jagraj was undoubtedly part of that first big wave of British Sikhs who re-discovered their religion. In a short space of time he went from the guy who loved partying at Punjabi weddings to the one who said it was wrong. Our family had a hard time adjusting to the new Jagraj. He became an amritdhari (baptised) and went to India to learn the Sikh scriptures. Not long after, his interest in religion became meshed with politics. He told me extravagant, but unconvincing, theories on how Hindu groups controlled top Sikh bodies (in those days the BJP and RSS could barely control their own affairs, let alone that of Sikhs).

After coming back from India he joined the British Army, got married and had a child. We used to joke in the family that Jagraj was always in a hurry and never did things slowly. Later his friends made the same jokes. To give you an idea of his passion, his honeymoon was not spent alone with his wife but on a pilgrimage to Hemkunt Sahib in the Himalayas. And he wanted me and his friend to come with them. We discussed politics and religion every day until we were exhausted. It was an amazing trip.

But the pressure and pace of change became too much. His first marriage fell apart and he lost custody of his son. He left the Army after four years and started a recruitment agency with a friend. My brother didn’t lack confidence or the willingness to take risks But despite problems in his personal life, he was relentless in his Sikh activism. That brought him in contact with Sukhmani Kaur, a Russian convert to Sikhism, whom he soon married. She was far more level-headed and grounded than he was and they built a family together in West London.

Preaching at the Golden Temple, in Amritsar

Preaching at the Golden Temple, in Amritsar

To start a revolution you have to first politicise people. You have to create the necessary conditions. That was Jagraj Singh’s plan all along. Luckily for him he was the right man at the right place at the right time.

Unlike Islam and Christianity, Sikhism isn’t a particularly evangelical religion. There aren't that many ‘preachers’ in the traditional sense, less so in Britain. Plus most Sikh institutions and preachers here were dominated by middle-aged men who didn't use English as their first language. There was a hunger, even among more middle-of-the-road British Sikhs, for knowledge and leadership that wasn’t being fed. Then came the rise of social media, which rewarded strong personalities and articulate voices.

My Oxford-educated brother stepped neatly into the role. He was charming, articulate and confident (sometimes too confident). And he was a breath of fresh air who knew how to communicate with younger Sikhs.

Jagraj Singh once told me he was inspired by the way I had used the internet to get into writing (it was the nicest compliment he ever paid me). Rather than slowly building up a name by preaching at Gurdwaras (he did that too), he went directly to the people using the web. He launched a YouTube channel to teach people the ‘basics of Sikhi’ so they would better understand the religion. But more than that he wanted to politicise them so they too would fight for social justice.

The project took off almost immediately as he was good at grabbing attention. And he was good at what he did. Basics of Sikhi started holding events and training sessions everywhere. They gave out leaflets on what Sikhism meant. They invited random people on the streets to ask them about Sikhs. They even started producing videos on Sikhism in different languages (drafting in my future wife for one in Spanish!).

From just a YouTube channel he quickly built up an army of supporters. When they wanted to raise funds for new projects, money poured in from all over the world. He launched the Sikh Press Association (to raise the profile of Sikh issues) and made plans to open up a big visitor and educational centre at the Golden Temple in Amritsar. His ambitions were only limited by his time and energy.

Preaching and debating at Hyde Park, London

Preaching and debating at Hyde Park, London

We used to chuckle when people posted incredulous messages on the internet asking whether Jagraj Singh and Sunny Hundal were really blood brothers. As he became prominent our worlds started clashing more frequently. Our parents were not happy.

Jagraj’s view was that Sikhs had to be purified. They had to be cleansed of bad habits and bad rituals, only then they could move forward. So while his main aim was to teach Sikhi to the masses, he was also intolerant of practices he interpreted as going against the scriptures. To take the most prominent example, he believed that Sikh theology did not sanction interfaith-marriages in Gurdwaras.

I had a different approach. I worry that religious people who try and forcibly ‘purify’ others can easily become authoritarian, violent and power-hungry. Once you start down that road, people start to criticise each other of not being pure enough and even more splits emerge. British Muslims went down that road and it hasn’t helped them one bit. Left-wing politics is also infected with the same culture and it has only led to more infighting and bad blood. I prefer the approach of the Jewish diaspora: accept that people will have different opinions and want to live their lives differently. Accommodate differences instead. On the inter-faith marriages controversy, rather than turning away Sikhs who wanted to marry outside the religion, I would rather their partners were welcomed and encouraged to learn more about Sikhi instead. This tension will continue to cause rupture amongst Sikhs, whether they like it or not. Today it is the issue of inter-faith marriages, tomorrow it will be over gay Sikhs. But I’ll leave that discussion for another article

It’s not that we wanted different things. Both of us were driven by a desire for social justice. Both of us are disruptors: we looked at institutions around us, didn't like what we saw, and decided to challenge them. We just had different approaches to that goal.

The genius of Jagraj Singh wasn’t his charisma or public speaking - they undoubtedly helped - but his foresight. One person can lead a revolution but to create real long-lasting change you need to create institutions. We all die one day but institutions can live on. They can help people for generations to come.

Death isn’t the end of life, it is a necessary part of the more important process of evolution. We all change a little bit during our lifetimes and then pass on our genes. Our offspring then carry on the same cycle and everything slowly evolves over thousands of years. Without death there would be no birth, no renewal and no change. There would only be slow decay. In that sense death is important as life, even if we greet the former with pain not celebration.

Jagraj Singh will leave behind a legacy in the form of his children and the institutions he created with others. It’s their job now to grow, evolve and build something new. I will carry the pain of losing my younger brother forever but at least in some ways he lives on.

----

I cannot end this without a tribute to Babban Singh, who tirelessly and selflessly helped Jagraj in his last months. The gratitude from our family will be forever endless.

Also, imagine the stress our mother went through, raising two highly opinionated and stubborn teenage boys in London? A big shout out to my lovely mum too